By Editor-in-Chief Padma Balaji, Web Editor Ekasha Sikka, and Staff Writers Erika Liu & Andy Zhang

MSJ’s Indigenous iconography is rooted in cultural insensitivity. For decades, the school’s logo and mascot have used symbols derived from stereotypical depictions of Native American people, both offensive and inaccurate to local Indigenous communities. Debate and calls for reform have and continue to define discussion surrounding the issue, pitting cultural sensitivity against school tradition. The Smoke Signal reviewed district records and its own archives to trace MSJ’s problematic history of appropriating Native culture from the earliest iterations of the Warriors mascot to the 1995 pow-wow controversy and finally to today’s national efforts toward discarding deeply-engrained prejudice.

Cultural Appropriation & Derogatory Representation (pre-1995)

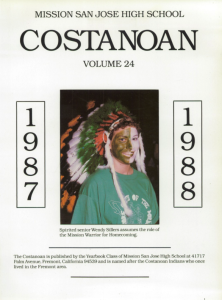

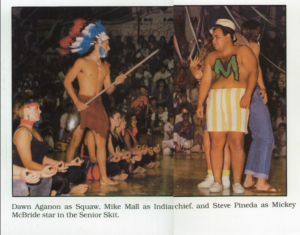

1987-88 edition of the Costanoan featuring student portraying redface. Photo by the Yearbook Archives

In 1964, when MSJ was first established, a steering committee designated to determine the school’s final mascot narrowed their options down to two choices: the Warriors and the Dons. “We knew that the Indians had a history in this area, as did the Dons, which was part of the Mexican culture,” JoAnn Dankwardt, a teacher on the original steering committee, said to the Smoke Signal in 1995. However, though Don is a Spanish honorific used to address nobles, it’s typically used for men from southern Europe, not Mexico. Eventually, the steering committee settled on the Warriors instead. “I imagine people picked it because it represented our area and it just seemed appropriate,” Dankwardt said.

The school eventually decided on the mascot of a Warrior, adopting a logo featuring a Native man in a headdress. However, the Warrior itself had little to do with representing local Native American tribes, instead playing into stereotypical depictions of Natives.

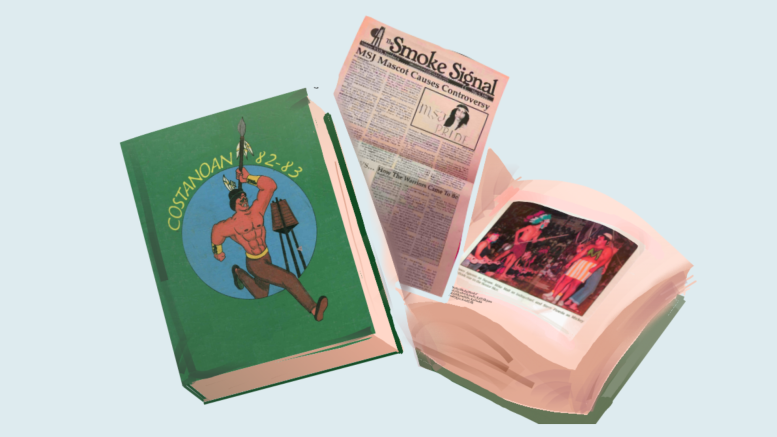

Throughout the time MSJ used its logo, racist and stereotypical interpretations of Indigenous people remained prominent in school culture. The 1987-88 Homecoming prominently featured redface in a senior skit, evidenced by the Costanoan issue of the same year. Other depictions of the Warrior mascot played into the “Magical Native American” stereotype, casting Natives as ethnic magicians closely linked to nature. This harmful trope was repurposed at MSJ as a symbol of school spirit: “The Warrior stirred … he toured the campus and spread his spirit everywhere … [he] blessed the teams and gave them strength,” alumnus Andy Stafford wrote in the preface for the 1982-83 Costanoan.

Even MSJ’s namesake, the Mission San José, serves to gloss over the violence that these institutions have historically perpetrated against Natives, local indigenous groups say. “Missions throughout California don’t always acknowledge the history of missionization, and they don’t acknowledge that there are still community members living that are direct descendants of the people who are missionized,” Muwekma Ohlone Youth Ambassador Isabella Gomez said. “Missionization led to [a lot] of violence. They only focus on missionization as just a glamorization of the church. But it’s important to talk about the people who are affected because of missionization.” According to Gomez, to date, sites like Mission San José continue to celebrate Missions as the beginning of Euro-American history without acknowledging Indigenous voices in the present day. “It is an odd situation being a public school named after a Catholic mission,” Athletic Director Freddy Saldaña said. “I went to a Catholic high school … so I’ve been educated on what a Mission represents and I know it’s in direct opposition to the Native American population and Native American communities.”

Fight to Change Indigenous Mascots

In February 1995, Native American parents and community members began voicing concerns over offensive mascots in FUSD. The Native American Parent Committee (NAPC) filed a complaint with the FUSD School Board, claiming the usage of Native mascots “perpetuates a stereotypical image which dehumanizes and damages self-esteem.” The letter urged the district to ban Native American mascots and logos permanently.

The growing controversy surrounding mascots came to a head with the pow-wow incident in 1995. When Irvington High School faced off against its rival school, MSJ, in a basketball game, Irvington students displayed a sign reading “Go team! Scalp the Warriors. Send them back to the reservation,” in reference to MSJ’s mascot. By coincidence, a pow-wow, gathering together more than 1,000 Native Americans across local areas, was held later that day in the same gym — where Native attendees were greeted with the hateful message the largely non-Native student population had prepared.

The following month, the board outlawed the use of “degrading” mascots, prompting reforms at MSJ and across the district. MSJ’s own Ethnic Race Relations Committee, established by Assistant Principal Dr. Miller in 1995 and active since at least 2010, recommended the school change the mascot. However, the school board failed to consult with or notify the student population of its final decision to discard the Native Warrior — embroiling the school’s mascot change in pushback.

Controversy Around the Mascot Erupts at MSJ

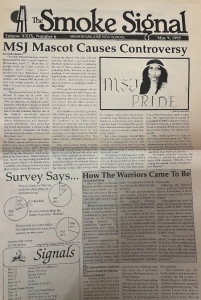

1995 column in the Smoke Signal about the selection of a new mascot for MSJ. Photo by the Smoke Signal Archives

Students successfully rallied to attend the following school board meeting, resulting in more than 150 MSJ students voicing their opinions at said gathering. According to a May 1995 poll conducted by the Smoke Signal, 89% of students surveyed said they didn’t think the Warrior mascot was “degrading” or “dehumanizing,” and 84% of students voted in favor of keeping it. “Mission has always been extremely respectful, [portraying] the Warrior in a noble, brave, and extremely dignified light,” Choctaw Indian Tribe Member alumna Angela Kendall said. “I do not feel that we are in a hostile environment and I want that to be very clear because my opinion was never asked.” Like Kendall, many students felt like their voices weren’t being heard, with 67% of students saying they didn’t have a fair opportunity to voice their opinion on the issue — exacerbating backlash from the student body against the mascot change.

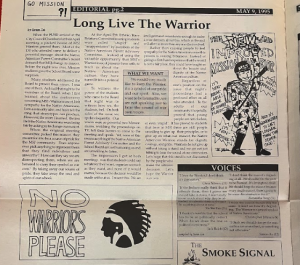

The survey was a part of the May 1995 issue of the Smoke Signal, a themed issue that focused on the mascot controversy. In addition to the survey, an editorial, graphic opinion cartoons, letters to the editors, and student voices were also included.

Supporters of the mascot denounced the change as a ploy to ensure “political correctness,” arguing designers never made the original Warrior with offensive intent. “The changing of the mascot is ridiculous,” then P.E. Department Head Tom Thomsen said. “We do not want to offend anybody, but it is my belief that the athletes and coaches have always been proud to be the ‘Warriors.’” For many students, the removal of a decades-cherished mascot felt like a personal attack. “By taking away our source of pride, they take away the soul and spirit of our school,” alumnus Erum Tai wrote in an editorial in the Smoke Signal on May 9, 1995.

However, Joe Barossa, chairman of the NAPC, argued the mascot fueled harmful misconceptions toward Indigenous people. “We’ve had enough of John Wayne shooting Indians,” Barossa said to the Mercury News on February 15, 1995. “The caricature that they use is demeaning and sinister-looking. It perpetuates the stereotypes you get from the movies.” Prominent 1950s actor John Wayne, whom Barossa referenced, is most notable in the film The Searchers, famous for its racially-fueled interpretation of the Texas-Indian wars. Wayne’s role popularized the “Warrior” stereotype, portraying Natives as savage or bloodthirsty in contrast to Europeans. MSJ’s mascot does nothing but reinforce this narrative.

The Smoke Signal’s May 1995 issue discusses student input on the selection of a new mascot. Photo by the Smoke Signal Archives

One alumnus, Jerry Underdal, stepped in to protest this, writing a letter to the Smoke Signal published on May 9, 1995, condemning the school’s current mascot. A Stanford University Alumnus, he cited the Stanford mascot’s own transition from the Indians to the Cardinals, urging MSJ to follow suit. “[Stanford] students didn’t make a big deal over the Indian theme, it was just there. We certainly didn’t make an effort to learn about real Indians,” Underdal wrote, highlighting the ignorance surrounding Indigenous themes. With a great deal of controversy, the issue was bound to reach a turning point.

To help MSJ students reach a consensus, the district hired Oakland-based consulting group Todos Consulting to help conduct student meetings and listening sessions. In the latter, a group of 70 students learned about the controversy and shared their views, meeting with several Native American leaders to gain their perspectives as well. “At first, most of the students felt pretty adamantly that we should keep our mascot,” Nathan Christensen, MSJ’s 1995 Junior Class President, said to the Mercury News. However, other students began to empathize with the Native American perspective following the Todos sessions. “It’s sort of patronizing to name [a person] as a mascot — equivalent to wolves and dogs. It’s degrading, even though it wasn’t meant to be,” Amir Shafaie, ASB President at the time, said.

Eventually, the school compromised, choosing to keep the name Warriors while exchanging the school logo’s Native “caricature” — as described by Barossa — for an image of Mission Peak.

Modern Shifts and Revisions

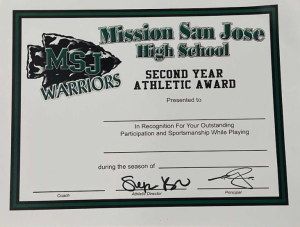

In accordance with changing attitudes and as a reflection of the shifting mindset concerning Indigenous symbols, offensive iconography has faded across MSJ. The school’s yearbook, formerly named the Costanoan — an anglicized label for the Ohlone people given by Spanish colonizers — has already been undergoing reforms, with its Instagram page currently changed to the Summit. In the same vein, in the 2024-25 school year, Saldaña worked alongside his Intro to Design students to rework the icons on athletic awards certificates to be culturally neutral. “One of my main objectives when I came to this job was to get rid of all Native American imagery in all athletics,” Saldaña said. This new initiative is one way he intends to bring closure to the issue.

AB 3074 and National Context

Starting in July 2026, CA Assembly Bill (AB) 3074 will create new restrictions for public school or athletic team names, logos, mascots, or nicknames. AB 3074 modifies the California Racial Mascots Act in the Education Code, expanding the definition of “derogatory Native American terms” to include any language or imagery referencing Native American people, cultures, or tribes in ways that may be inaccurate or demeaning. The bill requires non-tribal public schools to discontinue the use of such terms or imagery unless written approval from a federally recognized tribe is obtained.

AB 3074 mirrors trends across the country to reduce the academic appropriation of Native American culture. As of 2023, around 1,900 schools still utilize Indigenous mascots and names, including “Indians,” “Chiefs,” “Warriors,” and “R*dsk*ns.” At least seven states have passed laws restricting the use of Native mascots at any level. In New York, the state Department of Education threatened to withhold funding from a school district that refused to remove its Native American mascot, prompting a federal investigation into whether or not appropriation of racial mascots constitutes discrimination. Opposition has primarily come from the Trump administration, which launched an investigation into the state law. The effort was “an affront to our great Indian population,” according to President Donald Trump, who commented on the controversy on Truth Social.

In the Bay Area, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe has worked to remove offensive depictions of Indigenous people and statues of controversial figures. Last year, they worked with California State University, East Bay to rename the mascots from the Pioneers to the Peregrine Falcons, an animal indigenous to the area with roots in Ohlone culture and mythology. They also worked to rename a San José middle school from Burnett Middle School to Muwekma Ohlone Middle School. The school’s previous namesake, the CA governor from 1849-1851, Peter Hardeman Burnett, was a former slaveholder and pushed for the elimination of Indigenous people and exclusion of African Americans.

Although the support for name changes has been largely positive, Gomez says they still face pushback when trying to incorporate Ohlone history into CA missions. “We’ve seen Catholic churches not want to see any acknowledgement of actual California Native history in discussions of missionization,” Gomez said. “It’s just really hard when people don’t want to embrace that side of telling history as for what it really was.”

According to the Native American Rights Fund, the decades-long movement is meant to create learning environments where Indigenous students do not have to defend their culture. In 2008, a compilation of studies from the University of Arizona, Stanford University, and the University of Michigan found that exposure to stereotypical Native imagery and mascots may reduce Native American youth’s confidence in their academic potential.

“[Native mascots] really disconnect people from us as actual people in the present,” Gomez said. To people against mascot reforms, she expressed a desire for them to understand that “[it] is not a mascot. It’s a person, it’s a group and a community that is represented in that mascot. When you use it as a cartoonish figure, it disconnects people from understanding that it’s a human and a community that you’re representing.”

Yet, Native American voices remain underrepresented in these policies and decisions. “All too often the debate is a lot of non-Native people talking to a lot of non-Native people about how they think Native people feel,” Erik Stegman, an expert in Native American policy at the Center for American Progress, said to Edsource.

Remnants of Misrepresentation and Next Steps

Despite the steps MSJ has already taken to combat Native misrepresentation, cultural ignorance still lingers on campus. Athletic merchandise, as of now, continues to prominently feature spears, arrowheads, and shields in explicitly Native contexts. The MSJ Wrestling logo, featured on the team’s website, is a stoic, Native American warrior with a spear and a shield. Other emblems, such as the spiked “M” symbol, another major piece of school iconography, also draw from Native culture, with the “M” in particular being incredibly derivative of the Hawaii Rainbow Warriors’ icon, another indigenous symbol. However, Saldaña says there are steps MSJ can take to be respectful, noting that The Harker School installed a plaque in 2021 in honor of Muwekma Ohlone culture. Still, Saldaña says one of the biggest barriers to removing Indigenous imagery and recognizing local tribes is the cost. “It’ll take years to phase out [Indigenous imagery] … we have no money to buy or replace it,” Saldaña said.

Native populations today continue to face misrepresentation on a national level. Modern history curricula at MSJ remain, at best, “seriously lacking” in their reportage of Native history, according to World History Teacher Bill Jeffers. “Look at what’s happening on the reservations today,” Jeffers said. The textbooks fail to cover the twice-broken treaties of Fort Laramie, which should have granted Indigenous peoples a state within the US, or the Carlisle Industrial Indian School, an institution of mass forced conversion of Native children. Today, Native reservations consistently have the lowest graduation rates and the highest prevalence of drug abuse in the nation. “[These curricula] talk little about what happened in a meaningful way to Native people, and what continues to happen to Native people,” Jeffers said.

Discrimination against Indigenous populations is still deeply ingrained within school systems — both on a national level and in MSJ itself. Despite the steps the school has already taken to distance itself from culturally insensitive portrayals, MSJ’s historically problematic approach to Indigenous culture remains pervasive. Extant Native iconography around campus continues to fail to acknowledge the history behind reappropriated icons and names. Progress toward proper representation is long and slow; pushing for a stronger administrative stance on the issue remains necessary. “We should separate ourselves from Native American history and separate ourselves from the Mission,” Saldaña said. “We’re on Ohlone land right now … It’s something we should be more aware of.”

Be the first to comment on "Native American Cultural Appropriation at MSJ and the fight for change"